Somewhere after 2010, my life sped up and my memories slowed down.

The strange part is, on paper, everything looked better. Income higher. Work more interesting. Vacations more frequent. The phone got smarter, the internet faster, the apps more “seamless”. Yet there was this quiet, stubborn question that refused to go away:

If everything is better, why does my mind feel… thinner?

The Day Light Became Faster Than Thought

We live in a time where information practically travels at the speed of light. A war breaks out in Eastern Europe and, within minutes, a trader in Mumbai and an exporter in Gujarat are staring at red numbers on a screen, recalculating margins, watching their year shift in real time.

Earlier, distance softened reality. News took time. Impacts were delayed.

Now, a policy change in Washington can decide whether someone in Rajkot will expand their factory or shut it for good—before they’ve even finished their morning chai.

This isn’t just economics. It’s my nervous system being constantly pulled into events I am not physically part of. My brain was not wired for this kind of global, continuous partial involvement, and it is quietly rebelling.

The Illusion Of Being “A Call Away”

Take relationships, of example.

Earlier, if I missed my grandparents, I had only two options:

- Sit with the feeling

- Or physically go meet them

In that gap between longing and meeting, something important happened. My mind would replay old scenes. My grandmother’s laughter in the kitchen. My grandfather’s habit of pretending to be angry before breaking into a smile. Neurons fired, re-fired, strengthened connections. I was literally rebuilding the memory as I remembered it.

Today, if I miss someone, I press a green button. In two seconds, their face appears on a screen. No waiting. No space. No journey. My brain receives a quick hit of comfort and moves on.

Science calls the opposite of this “deep processing.” Memories that last are usually formed when the brain has time and space to pay attention, to feel, to connect dots. If everything is instantly gratified, the brain doesn’t bother laying down strong tracks. Why should it? There’s always another notification coming.

So yes, we are “a video call away”. But closeness has become something I stream, not something I grow. And streamed emotion doesn’t always settle into long-term memory. It buffers, plays, and vanishes.

Why My Brain Wakes Up With Pen And Paper

There is a small, unfashionable technology that still fights for me: pen and paper.

I feel more alive, more alert, when I write by hand instead of typing. The ones who practice it will quietly nod in agreement. Studies show that handwriting activates a far wider network of brain regions than typing: motor areas, spatial processing, and the hippocampus—the region central to forming new memories.

Typing, especially when done fast and automatically, is efficient but shallow. The fingers tap in repetitive patterns; the brain outsources half the effort. Handwriting, on the other hand, is gloriously slow. Each letter is a small act of drawing. My hand feels the friction, my eyes track the shape, my brain coordinates all of it.

In simple terms: when I pick up a pen, my brain understands that something is worth keeping. When I type, it sometimes behaves as if the information is “outsourced” to the device and doesn’t need prime real estate in my head.

No wonder my thoughts feel more real on paper. They literally leave a physical trace, both on the page and in my neural wiring.

Brain 2.0: Faster, But Thinner

Digital technology has done something subtle but massive to my mind.

Multiple studies now describe a pattern: constant streams of online information push my brain into a mode of fragmented attention—quick shifts, rapid refresh, shallow scanning. Over time, this shortens attention spans, makes deep focus feel uncomfortable, and disrupts how memories are consolidated and retrieved.

There’s even a popular phrase floating around research papers and newspapers now: “digital dementia”. Dramatic, maybe, but it captures a real concern—excessive screen time and information overload can lead to memory problems, poor concentration, and mental fatigue.

Interestingly, one study notes that this might not be a “decline” so much as a shift: my brain is adapting to handle quick, scattered bits of information at the cost of slower, deeper thinking. A brain optimised for refreshing feeds is not automatically good at sitting with one thing long enough to turn it into a lasting memory.

So when I say, “It feels like I stopped making memories after 2010,” there’s a very real mechanism behind that feeling. The problem isn’t that nothing meaningful happened. It’s that the speed and style of my days didn’t always give my brain permission to register that meaning.

The Konkan Beach Experiment

Then came that quiet trip.

No water sports. No curated “experiences”. Just a non-touristy stretch of the west coast of Maharashtra, the kind of place where the loudest sound at night is the sea arguing with the shore.

We stayed in a small house with a thatched roof that leaked slightly during the afternoon drizzle. The owner, an old man named Kaka, spoke only in Konkani and Marathi, and his idea of hospitality was to leave us alone with a kettle of hot water and a promise that the fish would be fresh.

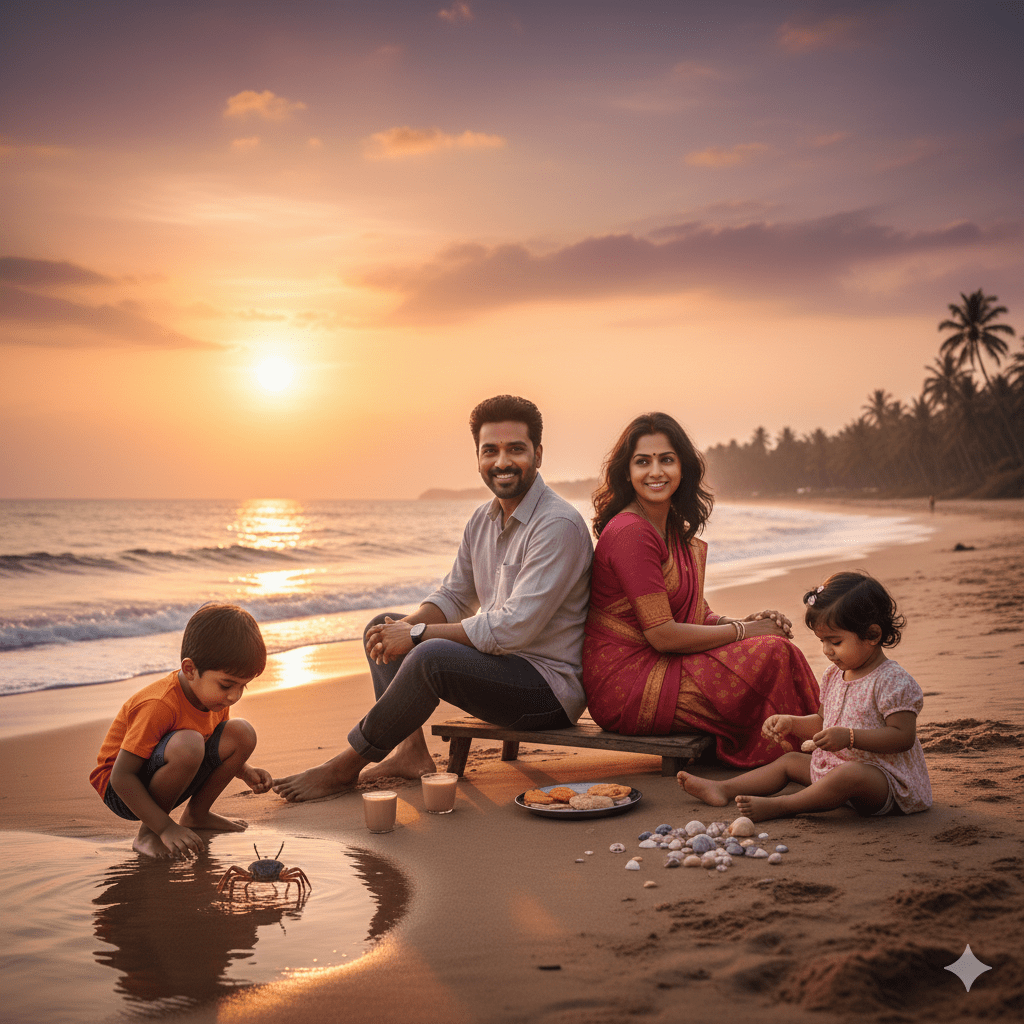

The first morning, my son—on the beach—discovered a crab. Not a picture. A real, sideways-walking, slightly annoyed crab. He spent alot of time just watching it move, he counted it’s legs and watched it make patterns on sand as it ran about. My daughter, found a broken shell and turned it into a treasure, a story, a whole universe that existed only in her head and the sand.

My wife and I sat on the beach as the sun went down, and for the first time in months, we talked without checking our phones. Not the usual “How was your day?” but the real stuff—her frustrations at work, the small victories she never mentioned because there was never time.

I noticed things I had stopped seeing: the exact way my son’s eyebrows furrow when he’s thinking, the particular pitch of my daughter’s laugh when she’s truly delighted, the way my wife’s voice softens when she’s talking about something that actually matters.

With no constant pings, my attention stopped being sliced into thin pieces. It could rest on one thing long enough:

- My son’s very specific style of mischief.

- My daughter’s way of testing limits and then checking if I’m watching.

- The way my wife talked about her work when there was finally time to listen beyond “How was your day?”

I didn’t “do” anything extraordinary. I simply removed the flood of competing inputs. I reduced the cognitive load—freeing up mental bandwidth so the brain can actually process and store what’s in front of it.

In ordinary language:

I stopped scrolling through life long enough to notice it. And the noticing itself became memory.

Slowing The River So The Stones Can Settle

Information today is not going to slow down for me. News will travel at light speed. Markets will respond in milliseconds. UPI will move money with a tap instead of a queue and a form. That part of the story is written.

But inside that story, I still have one quiet power: to slow the internal pace at which I expect my brain to live.

That might look like:

- Choosing pen and paper for thoughts that matter, so my brain understands: “Keep this.”

- Letting longing last a little before instantly calling, so memories can surface on their own.

- Taking vacations that are not about doing more activities, but about subtracting inputs.

- Creating small daily “Konkan beaches”: 30 minutes with no screens, just me, my people, and the day I’m actually living.

Maybe the question was never “Has time changed or has my brain changed?”

The better question might be:

“If information has become faster than ever, what do I need to slow down so that my life can still become memory?”

On that empty beach, with my kids plotting their next mischief and my wife finally finishing her sentences, I found one answer.

My brain remembers what I truly attend to.

The rest, no matter how “connected”, just scrolls away.

Leave a comment